The Day of the New Clan

Brothers and sisters of the tribe gather around a fire to hear the elders speak, as smoke slowly dissipates into the starry night sky. Drums beat a rhythmic story along with the constantly changing direction of the wind. Anticipation among them grows, awaiting a new saga of the pale skin foreigners their ancestors once encountered when cloud-ships first landed on the beaches of their homelands. Young children lean in closer, and closer, to hear their respected elder’s every word. The campfire reflects from the dilated pupils of the chief’s eyes, while mothers draw their babies in towards their bosom—every sentence lingers in the crisp air, and every word becomes imprinted onto the soul of the ears tuned in. To a mind that has never seen the billowing sails of an English ship, the Indigenous Americans saw only large clouds. The clouds—which carried the blessings of thunder and rain from the Gods—were, to their mind’s eye, the only thing strong enough, and powerful enough, to carry the weight of so many men so gently across the ocean’s surface. However captivating and enigmatic these large ships might have been, how terrifying the wonderment was, too. Wondering how these ships captured a cloud from the sky to use on the water…, they all gasp, as they are told of the ways their ancestors approached these clouds with a reserved intrigue. Surely, these beings must have been brought from the sky; and, for this, they must belong to the heavens…

The Original Settlers: Indigenous

In 1499, Amerigo Vespucci contradicts the account of Christopher Columbus’ 1942 “discovery” of America and maintains he landed on a separate continent altogether. This claim is confirmed, Columbus landed in the West Indies (the Bahamas & the Caribbean)—thus giving name to AMERICA.

In 1620, The Mayflower reaches contact with Plymouth Rock, after exploring Cape Cod and finding a harbor point. English Pilgrims pile ashore, disembarking from their 66-day journey from Plymouth, England. Plymouth Colony is founded, and settlement has begun. More settlers arrive in the new world, and 13 colonies are established along the eastern coastline. Later, in 1775, frustrated settlers of the colonies begin a revolution against the King of England.

On July 4th, 1776, a Declaration of Independence is presented to England via the new Representatives of the government of the United States of America. By 1803, after acquiring the Louisiana Purchase, President Thomas Jefferson began exploring west of the Mississippi River. Merriwether Lewis and William Clark set out with Native American guides, to traverse the unknown lands of the west. On August 3, 1804, The Otoe and Missouria Tribes were the first tribes west of the Mississippi River to host a council with Lewis and Clark (The present day city of Council Bluff, Iowa takes its name from this historic meeting). They hosted two official councils, with the second one being the only successful one, due to Lewis and Clark’s lack of understanding of the political structure of Indigenous nations.

In 1838 and 1839, the United States government established, through a series of Indian Removal Policies on behalf of President Andrew Jackson, the forced relocation of approximately 60,000 Indigenous Americans off of their homelands. Jackson was aiming for the forced removal of all Native populations east of the Mississippi River to maximize land expansion for white settlers. What would become known as “The Trail of Tears” by the Cherokee people—due to the amount of anguish and death the journey brought to their tribes—was eventually referred to as the Five Civilized Tribes (Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Cherokee, and Creek). With a starting point in the Appalachian Mountains (area including the states of North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama), and an ending point in the designated “Indian Territory” established in present-day Oklahoma, over 4,000 of the 15,000 Cherokee peoples died along the trail—leaving a trail of tears in the wake of their footsteps.

In 1845, Manifest Destiny took full hold among American politics, and full expansion into the west began—according to the advocates, destined by God, himself. In 1893, the Cherokee Outlet in Oklahoma (which remained mostly immune to the hardships of the red, white and blue battles during the Civil War) was eventually recognized by the federal government as a highly-valued plot of land, despite its reserved status as Indian Territory for the Native American Indian.

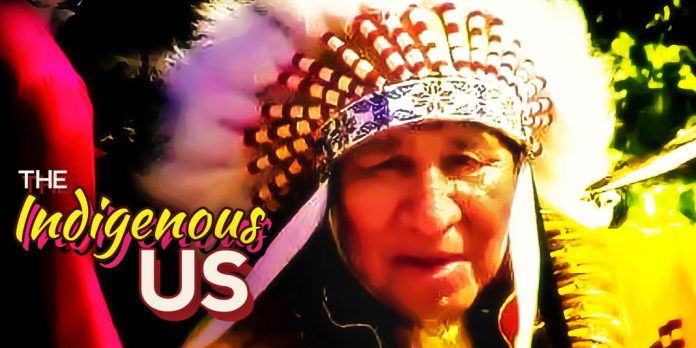

The New Day for Indigenous People

October 11th, 2021, President Joseph R. Biden signed a proclamation making Indigenous People’s Day a federally recognized holiday. “Our country was conceived on a promise of equality and opportunity for all people—a promise that, despite the extraordinary progress we have made through the years, we have never fully lived up to. That is especially true when it comes to upholding the rights and dignity of the indigenous people who were here long before the colonization of the Americas began”, President Biden says in the proclamation. “On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, our Nation celebrates the invaluable contributions and resilience of Indigenous Peoples, recognizes their inherent sovereignty, and commits to honoring the Federal Government’s trust and treat obligations to Tribal Nations.” This Tuesday, October 11th, 2022, will mark the second celebration of Indigenous Peoples Day as a federally recognized holiday in the United States of America.

Enid is home to many museums, and we—as a community—are quite fortunate to benefit from the opportunities we provide for those passing through Northwest Oklahoma. Jake Krumwiede explains an important reason why Indigenous Peoples’ Day is a vital holiday installment onto the United States of America’s yearly calendar; he states, “The ‘Cherokee Strip’ from our name is referring to the Cherokee Strip or Cherokee Outlet, which represents much of northwestern Oklahoma, which is land that the Cherokee Nation once had rights to.” As Museum Director for the Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center (located at 507 South Fourth Street in Enid, OK), Jake devotes his work life to sharing knowledge and spreading educational programs to the community. Jake shared his happiness to speak with Enid Monthly about this topic, easily generating a willingness to give a hand and offer connections to help develop this story for the community to benefit. Reinforcing the importance of shared connection and knowledge on even the dark subjects from history, continuing a tradition that has remained common among native cultures—story-telling.

The Cherokee Strip Museum in Enid shares the lives and stories of the re-settlement of Oklahoma lands, during a short series of events known as the Oklahoma Land Runs. The land Enid, OK rests on today was once the homeland to our Native American neighbors. With a history of Oklahoma being known as “Indian Territory”, Oklahoma, in itself, hosts a wide range of cultural museums with strong Native American origins and influences. Many Oklahoma towns found their own claim to fame in housing these museums; towns, such as; Tuskahoma (Choctaw Nation Museum), Wewoka (Seminole Nation Museum), Carnegie (Kiowa Tribal Museum), and Tahlequah (Cherokee Heritage Center) respectively pay tribute the native cultures housed within their walls. (Full List of Native Museums in Oklahoma can be found at the end of this article.) But, the narrative at this museum shares information on another part of American history. “Following the American Civil War, there was a lot of political pressure for the tribe to cede the Outlet back to the federal government, so the territory could be opened up for public settlement. The Cherokee Outlet Land Run of 1893 is when that occurred.” Jake continues, “to many indigenous peoples, land runs represent another example of broken promises from the U.S. government and lost land rights. Our museum…largely focuses on the settling of northwestern Oklahoma following the 1893 run.

The Elder Childs of Otoe-Missouria

Indigenous cultures have always valued gathering around the fire for stories, and they never shy away from telling the whole story—even if the truth isn’t something you always want to hear. Powwows are held yearly, and in Oklahoma, there is a variety of Nations (within our own Nation) you can visit to witness their cultures first-hand. Another form of a Native powwow is known as an “encampment”. Encampment is a time in which all Otoe-Missouria clans come together at the traditional encampment location in Red Rock, OK. This is all to serve their individual clan’s role. Each clan is responsible for a different part of the tribe, and this system means that each clan has a duty to fulfill to ensure the overall success of the event. Local Enid residents, The Childs family, belong to the Eagle clan, and the Eagle Clan oversees the ceremonies.

Marie Childs, before marriage to Henry Childs, was a member of the Bear clan. Being that Henry is Eagle clan, Marie inherited life among the Eagle clan as well as a loving, new family in her husband and eventual children Donnie, Johnnie, and Jana. Their son Donnie briefly explains how, according to Otoe-Missouria Legend, “the Bear clan and Eagle clan have always been two clans that have gotten along well, and marriage is common among these clans”. As the patriarch of the Childs, Henry was an admirable father to his children, a solid leader for the Eagle Clan, and a respected elder among the Otoe-Missouria Tribe. Beginning in the early to mid-nineties, Henry became encampment chair for the tribe and would hold the position for 24 years. A new chair is chosen every 2 years, and his respected performance allowed for Henry to be chosen a total of 12 times! Donnie would follow the flight of his father, and ascend to the same heights he once reached among the encampment hierarchy—he became encampment chair, himself. Shortly before the pandemic, Donnie went on to be selected for a second time. Marie stated in a post, “He [Donnie] makes his father so very proud that he followed in his footsteps. Donnie has always celebrated his Birthday during Encampment in July.” The struggles of the pandemic made hosting encampment difficult, but they found a way and the traditions continued. “We are so thankful we have good children. We are so proud of each of them, and now have Grandchildren that are making their own way in life….Storms make oaks take deeper roots,” Marie has stated.

After the stress of the pandemic encampment, Donnie stepped away from his role as chair to help care for his ailing hero, his father, Henry. “My father made eagle claw necklaces, but, no, it’s not a regular custom…[for each clan to have specific regalia relating to the animal representing their clan…although, it is customary for Otoe-Missouria to wear eagle feathers on their head,” Donnie states. Henry has been a respected elder and leader among the Otoe-Missouria tribe, and he has paved the way for the legacy to continue among his children and grandchildren, and certainly, generations to come. Donnie looks forward to re-seeking his place as encampment chair after he fulfills his duty to care for his father by being by his side during his final days. “Henry would be proud regarding our Otoe-Missouria encampment, his two daughters and granddaughter have served as our tribal princess in the past. He would also say that “being chairman is a “family affair.” He would thank his wife and all of his family for standing behind him during his terms,” said Donnie.

Aside from the wonderful things the Childs’ family have done for their tribe in Red Rock, they’ve always maintained a home in Enid, and enjoy calling our town their hometown. Jana Childs Rader is a softball coach for Enid High School, and all of the Childs have supported the Enid Plainsmen and Pacers. They all appreciate the representation Indigenous people receive from native imagery being used as a school or team mascot, although they agree there is a line between cultural representation versus exploitation. Donnie views the use of the term Plainsmen and Pacer for Enid High School as a very positive thing, for the most part, and believes his father feels the same way. He explains that he knows and understands the reasoning behind offensive mascots, but has enjoyed watching his own children grow up wearing the Plainsmen and Pacer jersey. Donnie says, “I’m very Proud to be Otoe-Missouria, and I’m very proud of our heritage and customs—I’m thankful every day to God that He has made me OTM. Enid has always been my home and my family’s home. The wonderful people of Enid have always accepted my family, and Enid has been a great place to live. Red Rock is where the tribe is, and where encampment happens every year, but Enid will always be ‘home’.”

I asked Donnie what his thoughts were about the new holiday, Indigenous Peoples’ Day, and his response was simple: “I’m an Indigenous American, so every day is Indigenous Day for me… and, I’m proud of that! I’m very proud to be Otoe-Missouria; I’m honored about sharing my heritage and customs.”

———————————————————————————————–

Indigenous Peoples’ Day

Who are you?

Where did you come from?

What cultures of peoples were brought together to form the tribes and stories, over time, to create the ‘you’ that is here today?

Do you know?

October 11th was declared a special recognition for the tribal roots removed in the days of early American settlers growing their own. This is a day to witness the beautiful intricacies of native cultures and customs; and, most importantly, the resilience of the indigenous tribes—who, through forced relocation and cultural assimilation, still managed to maintain a strong semblance of their own identity. The creation story, as told by legends of the Otoe-Missouria Tribe, is similar to the arrival of those new English ships anchoring on the shores of an Indigenous America.

When each new clan is discovered, it is added to the creation story narrative told among elders of the tribe—almost, as if, the clans of the Otoe-Missouria Tribe were meant to encounter along the timeline of their history. Similar to the unexpected scenarios encountered by Odysseus in Homer’s epic, The Odyssey—the Otoe-Missouria’s progressive legends within the creation story (and, the existence of the 7 Clans among the tribe, as a whole) are a telling of the human condition from the native perspective, specifically the experiences and beliefs of the Otoe-Missouria. They embrace the sharing of knowledge, both good and bad, with a rich history of culture-sharing and story-telling that continues today. Stories are a tradition passed along to the next generation—generation after generation. The Otoe-Missouria, and Native American Tribes alike, have remained loyal to their connections of the past. The Indigenous Tribes of the United States revere connecting the minds of their offspring, to the hearts of the kin running wild and free within the borders of their own veins. Ancestral tales lived long before are shared as a means of catharsis; and, often, a spiritual (and physical) warning to continue passing this knowledge.

The indigenous tribes across America approached the pale-skinned tribes aboard those ships with a blissful naivety. They soon found that the clouds they welcomed so earnestly were not clouds at all; and, they were certainly not from the Gods their people knew for so long. Many Native cultures worshipped a God that lived in the sky, in the ground, in the trees, among the flowers, and flowing along the rivers, cutting valleys through basins of rolling hills and mountain ridges. Even a gift that seemingly comes from the heavens can harbor a devastating hell.

The indigenous “us” lies within all of us, to some degree; but, the indigenous ‘U-S’ belongs to the native people of the United States. As the roots of American history grew among the lands of the new world, tribes native to America’s pre-English-colonialization era continued to experience hard-fought battles to retain the heritage and cultural roots of their own. This land, once borderless geography within shores of the “undiscovered” Americas, has more legacy among families like the Childs, and tribes such as the Otoe-Missouria. Indigenous People’s Day is in honor of the much-needed awareness for the sacrifices of life and society among native tribes along the timeline of settling this land, creating our home as it would become today.

“Some time passed before the Bear and Beaver Clans met other peoples, and the two were content to think no others existed. Then it happened.” According to the OTM Creation Story, “The Bear and the Beaver Clans came upon the Elks…then the sky people came through the sky opening and swooped down to earth, where they found evidence of three other clans: Eagle, Pigeon, Owl.” Then the Buffalo clan was the seventh clan to join the tribe. OMTribe.org states, “Today, there are seven surviving clans in the tribe. These are the Bear, Beaver, Elk, Eagle, Buffalo, Pigeon and Owl.” That is how the 7 Clans came to find one another, to eventually curate the Otoe-Missouria Tribes.”

Native American Museums in Oklahoma:

First Americans Museum – Oklahoma City

Oklahoma History Center – Oklahoma City

National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum – Oklahoma City

Sam Noble Museum – The University of Oklahoma, Norman

Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art – Norman

Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center – Spiro

Five Civilized Tribes Museum – Muskogee

Ataloa Lodge Museum – Muskogee

Indian City USA – Anadarko

Southern Plains Indian Museum – Anadarko

National Hall of Fame for Famous American Indians – Anadarko

Woolaroc Museum & Wildlife Preserve – Bartlesville

Cherokee National History Museum – Tahlequah

Cherokee Heritage Center – Tahlequah

Gilcrease Museum – Tulsa

Jim Thorpe House – Yale

Seminole Nation Museum – Wewoka

Choctaw Nation Museum – Tuskahoma

Sequoyah’s Cabin Museum – Akins

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center – Shawnee

Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center – Lawton

Washita Battlefield National Historic Site – Cheyenne

Museum of the Red River – Idabel

Saline Courthouse Museum – Rose

Museum of the Western Prairie – Altus

Creek National Capitol – Okmulgee

Chickasaw Cultural Center – Sulphur

Fort Washita Historic Site – Durant

Chocktaw Cultural Center – Durant

Semple Family Museum of Native American Art – Durant

Kiowa Tribal Museum – Carnegie